ENDLESS ORCHARD

Fallen Fruit is an art collaboration that uses fruit as a lens by which to see the world. All our projects are collaborative, forging unique art experiences that connect people to the places they live. This January, we were awarded a 2013 Creative Capital grant for “Endless Orchard” — a public installation of fruit trees in an urban setting that creates an orchard-like grove punctuated by mirrored surfaces, like a prism that creates an illusion of infinity. Our LA2050 proposal is to extend the orchard of fruit trees into the neighborhoods of Los Angeles County in a way that ultimately transforms the cityscape into a sparkling inhabited orchard.

This public installation contrasts the flashy technology of the spectacular with its opposite, the quietly growing abundant fruit tree. One is fast and complex, like a kaleidoscope, and the other is slow. One is all surface, and the other is all substance. But this is the idea: to see the relationship between our food and its history and how we live today. It interrogates our use of land, our values, and how we relate to one another. It asks us to take a close look, to see beyond the illusions the world presents us with.

With the support of LA2050, we can bring this concept to the next level by planting fruit trees in the adjacent neighborhoods to transform both their appearance and the way they function. It’s an immersive expansion of the Public Fruit Tree Adoption projects we’ve held in past years. Hundreds of bare-root fruit trees are given to residents through art spaces or cultural centers. These are gifts, and the recipients are asked to collaborate in the project: to care for the trees and to plant them on the border between private and public property, creating a resource to share with others. The abundance of these trees and their fruit creates a legacy for the communities of Los Angeles, with each block or neighborhood devising its own way to care and share for their informal orchard.

These Public Fruit Tree Adoptions transform a colorful idea into a vibrant reality. They literally root the necessity of healthy food and green space in the fabric of our daily lives. Some of these concepts have been prototyped in the newly dedicated Del Aire Public Fruit Park, in Hawthorne, CA. Fallen Fruit of Del Aire – Public Fruit Park is also the first public fruit park in the State of California. Still in its sapling stage, this park has already impacted the neighborhood of Del Aire in the shadow of LAX. Fallen Fruit planted 27 trees in the park itself, with 65 more distributed in the blocks surrounding it. This is the small-scale model for our much greater ambitions. We like to say that the point of art isn’t to describe what you want to see, but to make it.

Fallen Fruit’s series of Public Fruit Maps illustrates what already exists in our streets: surprising pockets of fruit trees that exist more through chance than planning — lucky, generous survivors of our urban ecology. Endless Orchard and our other public fruit parks enshrine these trees and creating a living kind of advocacy for an urban landscape. But in the end it’s not about art, and not about shrines. It’s about changing the nature of the city, putting nature back into the city, and imagining a topography that transforms the way we experience a place – both the familiar and the exploratory.

For Fallen Fruit, a piece of fruit is more than nourishment: it’s a symbol of culture, and a symbol of the basic social bonds not just between grower and consumer, but of the rituals of sharing and community. One of the places this symbol gets activated is in our ongoing series of Public Fruit Jams, in which groups of friends and strangers gather to make jam together, working collaboratively in a ritual that resembles the communal harvests of another epoch.

Fallen Fruit has worked with fruit, public space and the public for over 9 years. We have three tightly linked indicators for our project: Arts & Cultural Vitality, Environmental Quality, and Social Connectedness, and we do not want to separate them. We are artists whose work is a form of activism that examines the ecology and environment that surrounds us and uses the object of fruit to forge new and unexpected social connections.

Endless Orchard is a living public artwork that emanates from a defined focal point to suffuse the neighborhoods of Los Angeles County with change from the ground up, systematic change that transforms our conception of the city. It will take on a life of its own, possessed by no one and shared by everyone. By growing into the urban fabric it empowers people to change how they share resources, how they live daily life, and how they experience a city as great as Los Angeles.

What are some of your organization’s most important achievements to date?

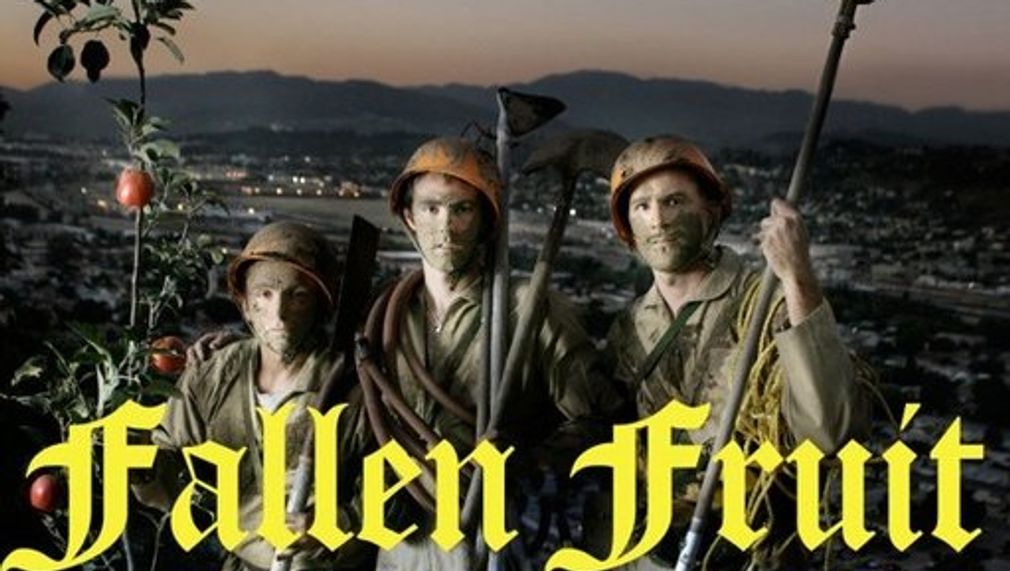

The three artists in Fallen Fruit, David Burns, Matias Viegener and Austin Young, have been developing their collaboration for nine years. We began simply by examining what was growing in our own neighborhood in Silver Lake, and we found numerous overlooked fruit trees, often a bit neglected, growing in or over public space. We mapped them, wrote manifestos about them, documented them and then brought people to see them.

Our neighborhood began to transform: more trees appeared and people started picking the fruit. We mapped other neighborhoods nationwide, and were invited around the world to create a range of work on things from the vast expanse of berries in the arctic to the contentious history of banana plantations in South America.

Our most ambitious project to date was EATLACMA, a yearlong residency at LACMA in 2010, which included an exhibition, five artist-commissioned gardens, several events including two Public Fruit Adoptions, and a day-long curated performance and intervention in the museum’s spaces that broke attendance records. It was funded in part by a $100,000 MetLife Foundation Community Connections Grant, and received over 100 million press impressions. EATLACMA included our Public Fruit Theater, an intimate amphitheater built with recycled city sidewalks around an orange tree, which delivered a slow and beautiful performance of the seasons: blooming, leafing and fruiting.

In the last three years we’ve had two projects titled Accion Fruta Urbana, one in Tijuana, Mexico, and the other in Madrid, Spain, as part of ARCO 2010. In the latter, we worked to populate a working-class quarter of the city with 50 fruit trees. Temporarily impeded by an uncooperative municipal government, the trees found a home in a communal park, Esta es una plaza. The project was accompanied by a billboard and bus shelter campaign in over 300 locations, which contributed tremendously to raising public consciousness.

Most recently, we completed the new Del Aire Public Fruit Park in Hawthorne, near the intersection of the 405 and 105 freeways. Funded by an award from the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, the park is planted with an “eye” of 27 fruit trees, with 65 trees “adopted” and planted by residents in the neighboring streets. It received a tremendous reception in the press, and KCET is currently shooting a documentary on the park and our collaboration.

The proposal for Endless Orchard is the recipient of a 2013 Creative Capital award, which will bring in at least $50,000 in funding for the project. Though this is not its full budget, it offers us a remarkable level of professional support in seeking out further funding and development.

Please identify any partners or collaborators who will work with you on this project.

We’ve just begun looking for the right site for Endless Orchard. Through our experience with the Del Aire Public Fruit Park, we are on good working terms with the departments of Parks & Recreation, Health & Safety, and the DWP. We have incredible support across broadcast media, museums and public institutions throughout Southern California. We work with groups such as the Los Angeles Urban Rangers and Food Forward, an activist group that practices “fruitanthropy,” gleaning fruit from neglected trees on private property & distributing it to the needy. We have long-term relationships with Treepeople LA, Projecto Jardin, the Metabolic Studio, Watts House Project, Watts Towers/Grand Central Arts Center, USC, UCLA, LACMA, and the Hammer.

Please explain how you will evaluate your project. How will you measure success?

The most essential measure of this project is the level of participation: the number of people who adopt trees and plant them on the boundary of public and private, as well as the far greater public who sees these trees and starts to think about what they might mean. This is the way people create a new public — not one we as artists have created, but one they create with each other. This public has an evolving consciousness of urban life and how it must change to become more habitable.

The simplest measure of the project’s success is to keep a count of the neighborhood’s fruit trees, which is part of the goal of our Public Fruit Maps. Every neighborhood we’ve made maps in has seen an increase in fruit trees, and we believe in part that’s because the map focalizes people attention. It raises consciousness, and presents a vision of what might be that suffuses what is already there.

Other measures of the success are more mechanical: Google-type metrics, broadcast media impression and public participation. While watching neighborhoods transform, what cannot be quantified is how people feel. We believe that fruit trees are a powerful symbol, and the symbol extends outwards from the actual presence of trees into the way they enter public consciousness. We’ve had great publicity over the years, and our media base is constantly growing.

How will your project benefit Los Angeles?

This project is uniquely tied to Los Angeles by history. Much of the land on which the city is built was once citrus orchards, most of them razed over the last century for building sites. Almost the only trace that remains is in old postcards of endless orchards with a backdrop of snow-covered mountains, the vigorous fruit contrasting against the icy peaks. These cards fed the utopian dream of California, a bountiful place where you could live in beauty and comfort.

Fallen Fruit’s work has often alluded to this past, a way of holding on to a utopian impulse in the middle of our urban grit. It comes with echoes of democracy, the idea of a just world in which everyone is treated equally and everyone’s needs are accounted for.

California has a complicated history, from its first colonization by Spanish missionaries to the rancho system, where land tracts were given to favored people as rewards, and then the Homestead Act, which tried to democratize things. One of the ideas of old West we respect was to take care of strangers and passersby — in a world without infrastructure, all people had was each other.

Los Angeles is now bursting with infrastructure, and a lot of it doesn’t work. We have less public green space per square mile than New York City. The idea of the commons was never particularly Californian, but it’s rooted in human culture: a space that’s shared by all, not just to look at but to graze our animals and raise our food. The commons weren’t about ownership (which was shared) but about use: who could use the land and the things it gives us.

Fallen Fruit’s public art projects have really arisen in the context of Los Angeles and its strange mix of density and neglect. The public agrarian experiments we propose are uniquely suited to our climate — not just the weather but also the culture. Fruit is a great tool for socially-minded artists because it never exists in isolation. Someone grows it (often in California), someone picks it (often an underpaid migrant worker), and others prepare it, serve it, and then consume it. Our work strives to connect all these relationships in surprising ways.

None of the fruit commonly eaten today is native to California, though much of it is grown here. We work with that fact, and see the way a bunch of fruit hanging over the sidewalk in Alhambra is also an invitation. It’s a symbol of bounty and generosity. It’s an invitation to a stranger, perhaps to you.

What would success look like in the year 2050 regarding your indicator?

Forty years from now, Los Angeles would have a completely different landscape. All arable land would be adapted to generate fruit and produce. The city would be a kind of permaculture food forest. This doesn’t mean that it won’t be beautiful. We take advantage of the natural beauty of fruit and fruit trees, the fragrance of their flowers, and the soothing charm of their green leaves — all demonstrated to improve mood and quality of life.

The outlook at the moment is grim. Southern California shows the highest rates of growth in California, the fastest growing state in the country. LA County will increase by 3.5 million people by 2050 while neighboring Riverside County to the east will follow closely, adding almost 3.2 million people. LA will continue to be the largest county in the state, topping the 13 million mark by mid-century.

Many of the metrics in the LA2050 Report are interrelated in complex and subtle ways. Cultural vitality stimulates education by provoking young people’s curiosity in the world around them; good education opens the way to good jobs. Environmental quality and social connectedness impact health, which lays the ground for a good life, and our housing improves when our neighborhoods improve because happy, healthy people care about them.

In 2050 we want an integrated planning system that takes all our needs into consideration, without making every place or every person the same. Our needs include how we eat to how we work and share space together, needs that are material, and linked to health, to needs that are elusive, like the effect of natural beauty or a perfumed breeze. The vision we propose is poetic perhaps, but it is rooted in this place, and its ambitions are social, political and utopian.